Learning a foreign language is always a challenge. However, in the process, we sometimes come to realize just how complex our native language can be. In this blog, I’d like to share some thoughts on the intricate ways Japanese speakers use personal pronouns, especially for referring to oneself and others, which can be quite confusing for learners of the language.

How to Refer to Yourself and Others in Japanese

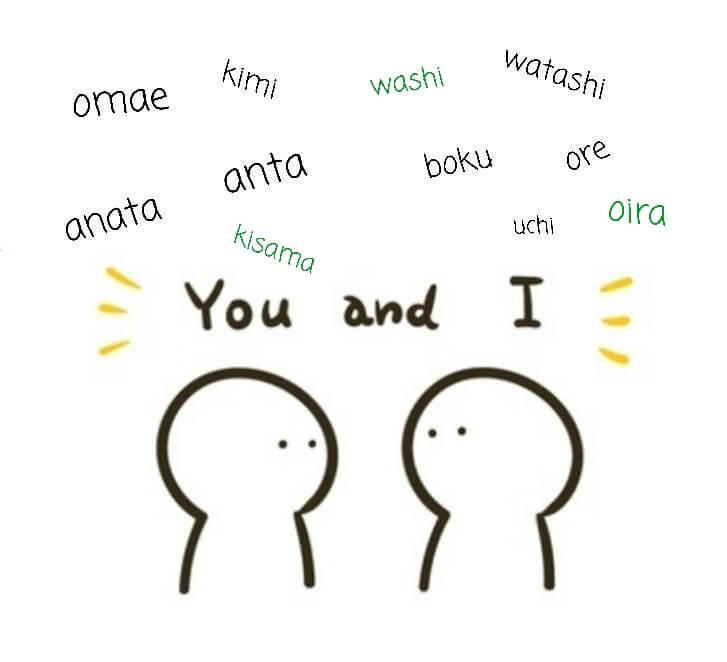

In English, the first-person pronoun is simply “I,” regardless of formality, gender, or social role. In contrast, Japanese offers a rich variety of first-person pronouns—such as watashi (私), boku (僕), and ore (俺)—each carrying different nuances related to formality, gender identity, and personality.

If you’re a fan of Japanese anime, you may have noticed that first-person pronouns are often used deliberately to highlight a character’s personality or background. For example, Shinnosuke from Crayon Shin-chan refers to himself as oira, a rustic and cheeky-sounding pronoun that gives off a mischievous, playful vibe.

In fact, no one knows exactly how many first-person pronouns exist in Japanese. There may be dozens, especially if you include regional variations and archaic forms.

Japanese speakers also use a range of second-person pronouns and titles, such as anata (あなた), kimi (君), and omae (お前), as well as name-plus-honorific combinations like Yamada-san (山田さん), depending on the relationship and context.

In my view, addressing someone as anata can sometimes be distant or cold. Japanese people often prefer to refer to the person that they are speaking to by name, or simply omit the subject when the context is clear.

Here is a list of common examples and nuances for first-person pronouns:

| Pronoun | Romaji | Common Users / Nuance |

| 私 | watashi /watakushi | Gender-neutral. Polite and formal. |

| 僕 | boku | Typically used by men. Polite, soft, and somewhat modest. |

| 俺 | ore | Male, casual. Stronger and more masculine. |

| 自分 | jibun | Can sound humble or neutral. Used in sports or by men in casual talk. |

| あたし | atashi | Feminine and casual. Used by women in informal situations. |

| うち | uchi | Common among women and in the Kansai region. Friendly and casual tone. |

| 俺様 | oresama | Used by arrogant and overconfident characters. Often used in anime for comedic effect. |

Here is a list of common examples and nuances for second-person pronouns:

| Pronoun | Romaji | Common Users / Nuance |

| あなた | anata | Neutral and polite. Often used between strangers or in formal speech. |

| 君 | kimi | Casual, often used by men toward juniors or close friends. Sounds intimate but also condescending, depending on tone. |

| お前 | omae | Casual to rough. Used by men with close friends or subordinates. Often sounds rude if used incorrectly. |

| あんた | anta | Very casual and blunt. Common in Kansai dialect or emotional speech. |

| お主 | onushi | Archaic or theatrical. Used in samurai-era settings or fantasy/anime for effect. |

| 貴様 | kisama | Extremely rude today. Originally polite in historical usage. Now often used in anime or confrontational speech. |

| [Name]+さん | [Name]+san | The most common and polite way to address someone. |

Self-Reference within the Family

Let me show you another example that is unique to Japan. In Japanese households, it is common for parents and older siblings to refer to themselves using role-based titles, such as Mama or Okā-san (mother), Papa or Otō-san (father), Onii-chan (big brother), and Onē-chan (big sister). For instance, a mother might say “Mama wa ureshii yo” (Mama is happy) rather than “I’m happy”. This phrase is used not only when speaking to her children, but also to her husband.

This style of self-reference is based on the concept of a child-centered approach to communication. By using the same terms as children, adults can create a more accessible and emotionally close environment. This also reinforces the child’s understanding of family roles and relationships.

Additionally, you might find it weird to hear that married couples don’t address each other by their names, but rather as Otō-san or Okā-san in the household. In recent years, however, some Japanese families, especially younger or more Westernized ones, have started using each other’s first names. However, this is still relatively uncommon. Traditional, role-based titles remain the norm in most families.

How Spouses Refer to Each Other

Next, I’d like to discuss the words used in Japanese when referring to one’s spouse in conversation. In English, people generally just say “my husband” or “my wife.” But in Japanese, there are many different terms, each with subtle social and historical connotations.

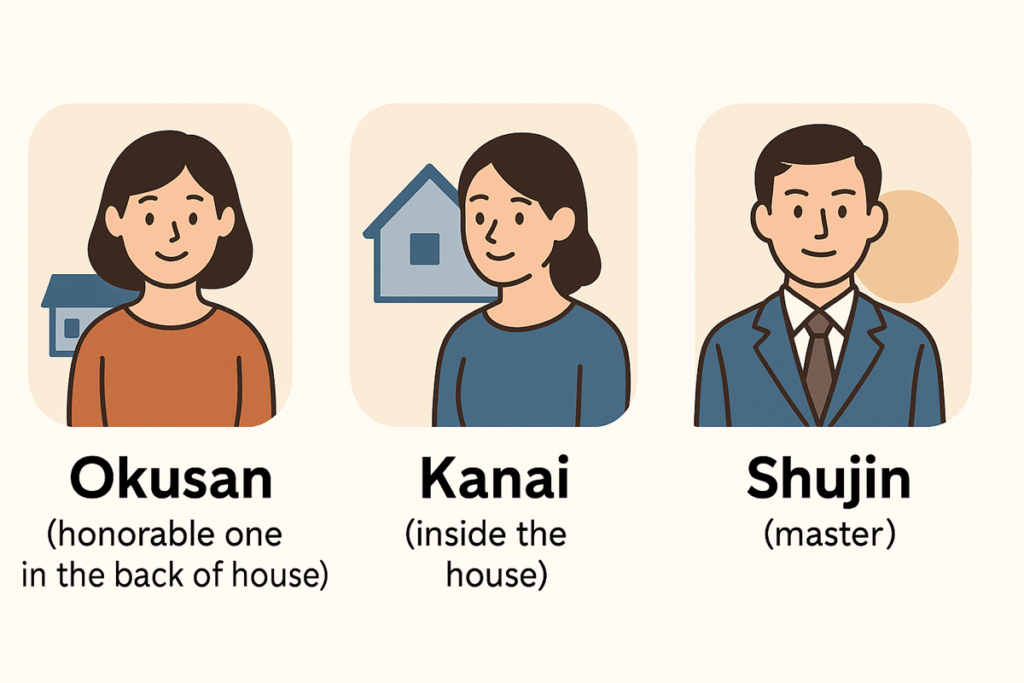

Although neutral words like otto (夫 husband) and tsuma (妻 wife) have become more common in recent years, they have been used only in writing or official speech. Still, traditional expressions such as shujin (主人), danna (旦那), okusan (奥さん), and kanai (家内) are widely used — often unconsciously. These words reflect historical gender roles and social expectations. Let’s take a closer look.

| Japanese Term | Romaji | Refers to | Literal meaning / Origin | Nuance / Usage Notes |

| 夫 | otto | husband | Just “husband” | Neutral and modern. Often used in writing or official speech. |

| 主人 | shujin | husband | “Master” or “head of the household” | Traditional and still widely used, but criticized for reinforcing outdated gender roles. |

| 旦那 | danna | husband | Originally a term for patrons. | Informal and casual. Common in conversation, but some feel it sounds too laid-back or unrefined. |

| 妻 | tsuma | wife | Just “wife” | Neutral and modern. Used in formal speech and writing. |

| 家内 | kanai | wife | “Inside the house” | Traditional. Reflects the idea that the wife stays at home. Still common, but increasingly seen as outdated. |

| 奥さん | okusan | wife (also someone else’s) | An honorable person in the back of the house. | Polite and widely used. Can refer to one’s own or someone else’s wife. Common in everyday conversation. |

| 嫁 | yome | daughter-in-law / sometimes wife | Traditionally wife of one’s son | In modern speech, sometimes used casually to refer to one’s wife, but older generations may see it as incorrect or impolite. |

As you can see from the table above, most of the terms other than otto (husband) and tsuma (wife) reflect traditional Japanese views of family roles. Many of them are no longer considered appropriate in today’s society. Nevertheless, most people who use these expressions do so unconsciously without any intention of reinforcing outdated values.

Referring to Someone Else’s Spouse

Last but not least, I’d like to touch on the area that causes the most confusion for Japanese speakers: how to refer to someone else’s spouse.

In English, it’s simple — you can just say ‘your husband’ or ‘your wife.’ But in Japanese, using words like otto (husband) or tsuma (wife) when referring to someone else’s spouse often feels direct or rather awkward. Instead, people usually use more polite expressions like goshujin (ご主人) for someone’s husband, or okusan (奥さん) for someone’s wife. For example, you might say: “Goshujin wa ogenki desu ka?” (“Is your husband doing well?”).

These expressions are widely used and considered polite. However, they also reflect outdated social norms and gender roles. I wish there were a more neutral and modern option — something as simple as English.

Personal Note

It is interesting to look into the origins of words. Language constantly evolves — some expressions fall out of use, others shift in meaning, and many are used unconsciously without awareness of their historical background.

As a Japanese-speaking English learner, I admire how simple English can be. However, I also find it fascinating that our everyday Japanese expressions still quietly carry stories from the past.

Lives in Takatsuki city, Osaka. Has been engaged in English for work and fun for years.

HTJ has a YouTube page! Check it out

HTJ has a YouTube page! Check it out

Hi Mami-chan! We all talked about this article on LINE in Japanese, but thanks again for such a thoughtful and deep article.

When I moved to Osaka, I was really surprised that people use “jibun” as the second-person pronoun! I haven’t heard much about it lately, though. I wonder if it’s still common in the southern part of Osaka?

Like you said, it’d be nice to have a good way to refer to someone’s husband or wife. Calling them by their name, like in America, might be the best way. But how do they manage to remember so many names? That’s amazing, isn’t it!?

Thank you for your comment, Aki-chan! Yes! You’re right! “Jibun” can be used as a first- or second-person pronoun. I don’t use it, though.

Haha! Which is easier to remember, so many kinds of pronouns in Japanese or people’s names?