“Tsuki-mi” (月見), literally meaning “to look at the moon,” depicts the traditional moon-viewing events or autumnal customs in Japan. Since Japan has four distinct seasons, people have cherished the seasonal taste which deeply exists in our hearts. Now let us trace the history of Tsukimi and pick up its influence in our life.

The beginning of Tsukimi

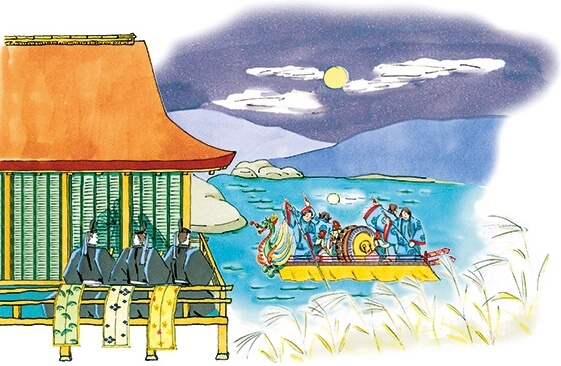

Tsukimi dates back to the Nara period (710-794 AD), but it didn’t become a formal celebration until the Heian period (794-1185). It was inspired by the custom of moon-viewing in Tang Dynasty China (618-907) and was taken up by Japan’s aristocrats who would play music and compose poetry at parties in the moonlight. They would also take boats out at night to view the moon reflected in the water.

Two opportunities for moon viewing

In the lunar calendar, people celebrate the full moon on August 15 (Jugoya, 十五夜). Emperor Daigo (醍醐天皇, 885 – 930) was supposed to introduce this custom. Later, he added one more opportunity to savor Tsukimi on September 13th (Jusanya, 十三夜) because the moon at this phase is also beautiful to watch and the weather was stable in September in the lunar calendar at that time.

Jusanya (十三夜) is the Japanese original Tsukimi, and we have a double-chance to watch the beautiful moon at night. This tradition was passed on to the next generations and later combined with the harvest thanksgiving events by the ordinary people.

Tsukimi in Edo period

In the Edo period (1603-1868), Tsukimi was popular amongst all classes, including farmers. By this time, the festival had become more closely associated with other autumn traditions, in particular, thanking the deities for a bountiful harvest and praying for a successful year to come.

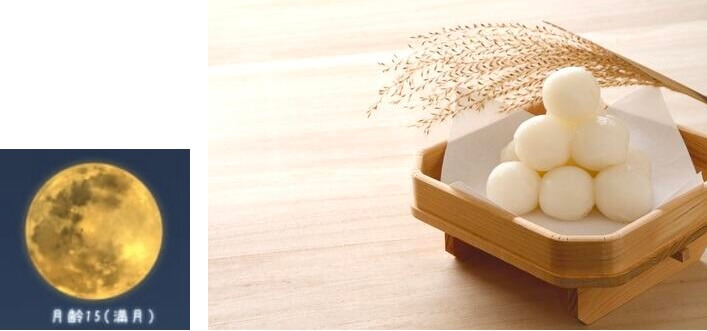

People placed offerings such as Tsukimi dango; moon viewing dumplings, susuki (Japanese pampas grass), and the grains as that year’s harvests. Dumplings represent the hopes of an abundant harvest in the coming year, and susuki is a wish for bountiful harvest and is believed to ward off evil.

Jugo-ya (十五夜), the full moon on August 15th

Based on the lunar calendar, July, August, and September represent the fall season. They are called Shoshu (初秋), Chushu (仲秋), and Banshu (晩秋). The very middle of the entire fall is also called “chushu” but uses different kanji: (中秋). This chushu means “August 15.” Supposedly, we can expect to watch the full moon in the sky. We call it the best moon in the middle of the fall (中秋の名月). On this day, fifteen moon-viewing dumplings are placed, and taro, a kind of root vegetable, is specially placed with other grains. So this day is also called Imo Meigetsu (芋名月).

Jusan-ya (十三夜), a beautiful moon on September 13th

Tsukimi on this day is a Japanese special, not a tradition in China. Though it is not a full moon, people have cherished this style of the moon. On this day, thirteen moon-viewing dumplings and chestnuts are placed because it is the harvest time of these foods. So this day is also called Kuri Meigetsu (栗名月)

These two opportunities for Tsukimi are set activities which people should keep doing every year. So in Edo period, if people failed to do one of these Tsukimi, it was called Kata Tsukimi (片月見); missing a Tsukimi should be avoided!

Tokan-ya (十日夜), a harvest festival on October 10th

To do Tsukimi on a harvest festival on this day is a custom in eastern Japan. This time is the harvest time of rice. Thanking deities for the harvest at this time was combined with moon viewing. People placed offerings near the scarecrow in the field and wished for the great harvest next year.

Nijuroku-ya (二十六夜), a thin phased moon associated with three deities on July 26th

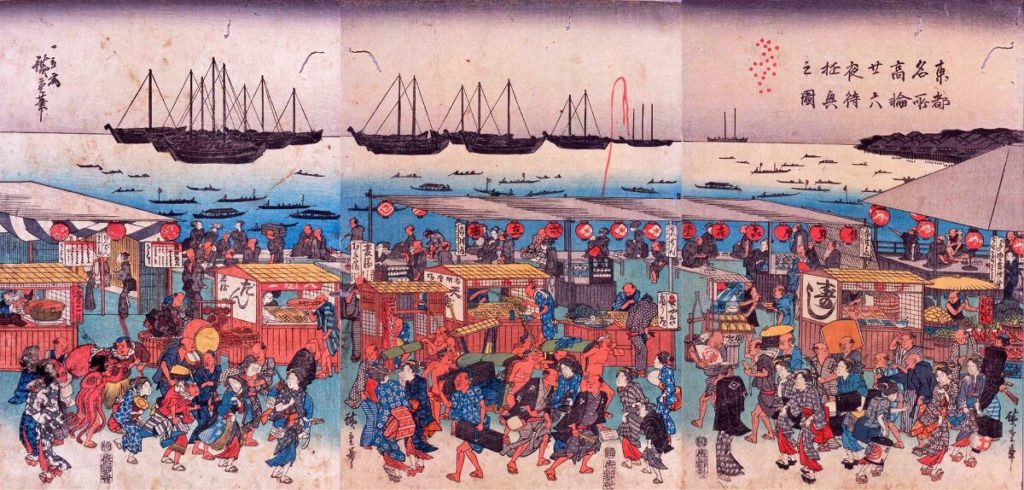

On this day, they said that the Amida Triad would appear around midnight in the sky with the moon. People believed that and waited for the moon to rise until midnight.

However, this episode shows the personality of the people of Edo. Please look at the Ukiyoe picture below. This picture depicts many people gathered and enjoyed eating out, and they looked like they were holding a boisterous party. It was true!

In this case of Nijurokuyamachi, Tsukimi was a good excuse for them to go out, get together, and have a good time outside in summer. In this picture, some food stalls such as sushi, tempura, dumplings, and others are drawn. It was a precursor of the Japanese matsuri festival.

Contemporary Tsukimi in Japan

We should be careful that Tsukimi is totally based on the lunar calendar. Now that we live our daily life by solar calendar, we would be confused which day is for Tsukimi.

Many people already know that Tsukimi is on August 15, but it is true only in the lunar calendar. It is quite a complicated fact to recognize, but one thing is clear. Even though our life in Japan was drastically changed after the Meiji restoration (明治維新), people have still cherished the traditional Japanese lifestyle. We accepted westernization but never lost our originality.

Katsura Rikyu (桂離宮), a special place for moon viewing

Katsura Rikyu in Kyoto, built in the 17th century, has a profound connection with the moon. For the ancient Japanese, the waxing and waning of the moon was considered to be a symbol of rebirth. In fact, because many of its rooms were specifically laid out so that they would provide a good view of the moon, the whole complex was designed as a large moon-viewing facility.

The picture below is the full moon as seen from the Katsura Rikyu in October. Once the moon had risen high in the sky, the guests would move to this moon-viewing platform in a different building. Reflected in the surface of the pond, the full moon creates an enchanting “double moon” effect.

Ginkakuji (銀閣寺), a place for Tsukimi?

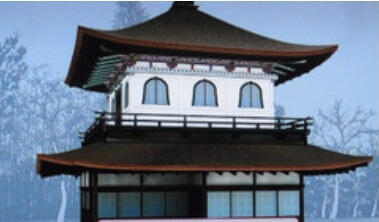

Ginkakuji (銀閣寺) in Kyoto, built in 1482, also had a close relationship with Tsukimi. It was built as a hideout for 8th Shogun Ashikaga Yoshimasa of Muromachi Shogunate.

The name Ginkaku literally means “silver pavilion;” however, there is no evidence of silver decoration on this building. Then, why is this building called “the silver pavilion”?

Recent survey shows a very interesting story: there was a possibility that Ginkaku was decorated by white clay so that it reflected the moonlight. It would be lightened up by the moonlight accompanied with its white sand garden which also would shine in the moonlight.

It is still imagination, however, Ginkakuji was obviously designed for moon viewing, and it is possible that Shogun Yoshimasa had a strong affinity for moons viewing. It should be called a moon viewing pavilion at night.

Moon and Rabbit

a crow in the sun & the rabbit in the moon

A rabbit is preparing a powdered drug with a mortar and pestle

Why is the rabbit connected to the moon?

It is possible that several episodes are combined together to create this image.

- In ancient India and China, a rabbit was believed to be living on the moon.

- In Chinese legends, rabbits are making a miracle cure (妙薬) by using a mortar and pestle.

- In Chinese, “full moon” is “望月,” (bougetu or mochizuki), which sounds like “餅つき” (Mochitsuki) for Japanese people.

Probably these three episodes are combined together and became the image of rabbits on the moon.

Conclusion

Tsukimi has been and will be an important tradition and will continue to be passed down in several ways. That is because Japanese people are originally very good at preserving and improving their culture, even when it’s sometimes something which no one has ever created before.

We could say that Japanese people have been communicating with the moon since ancient times.

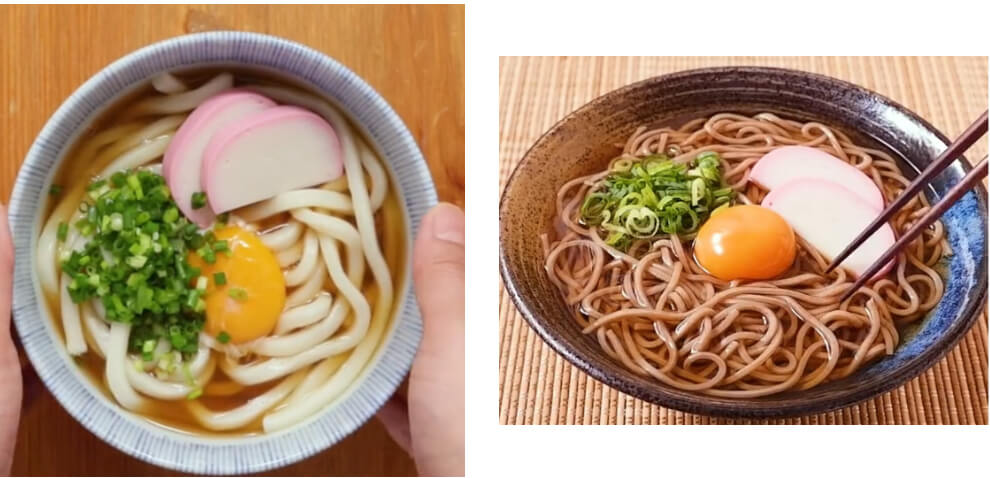

Egg yolk plays a role of full moon

National Tour Guide (English), Eiken Grade 1, TOEIC A rank. Have been studying and teaching English for over 30 years.

HTJ has a YouTube page! Check it out

HTJ has a YouTube page! Check it out

Hi, Takeshi san!

Did you enjoy the total lunar eclipse the other day?

I worked overtime then, but I enjoyed it with my boss and colleagues from our office.

It was a different mood like a festival compared to usual Tsukimi.

Usual Tsukimi is a calm and beautiful culture, isn’t it?

After reading your article, I thought the long history of Tsukimi has brought us the special feeling to a beautiful moon.

Thank you for sharing a lot of Tsukimi history.

I like Japanese people imagining round shaped food as the moon, too!

Akiko san

Thank you very much for reading my article and sharing your views on moon viewings.

And I’m glad to know that my article played a little assistance for you to savor the moon viewing in various ways.

I did enjoy watching total eclipse of the moon the other day! Moon and constellation has been filled with a sense of wonder and especially moon lives deeply in our hearts…