Imagine attending a class reunion and spotting someone you recognize, but you just can’t recall his name. Who is he? It’s on the tip of my tongue! This expression is common in English. Interestingly, in Japanese, the phrase is “It’s almost there in my throat” (のどまで出かかっている nodo made dekakatteiru). The meaning is the same, but the way of expressing it is different.

It’s interesting how different languages use different ways to express the same idea. Learning a foreign language is not only about words and grammar – it also opens the door to understanding the culture behind those words. Proverbs and sayings, in particular, have been passed down for generations, and by exploring their origins, we can gain deeper insights into the history and values of a culture. In this blog, I would like to introduce Japanese proverbs and expressions and compare them with their English counterparts.

When you’re swamped with work and wish someone could give you a hand, you can say, 猫の手も借りたい (neko no te mo karitai). The literal meaning is “I want to borrow even a cat’s paw.” You might wonder, why a cat’s paw? Since cats are thought to be fickle and not very helpful, this expression describes a desperate situation where you would accept help from anyone, no matter who it is.

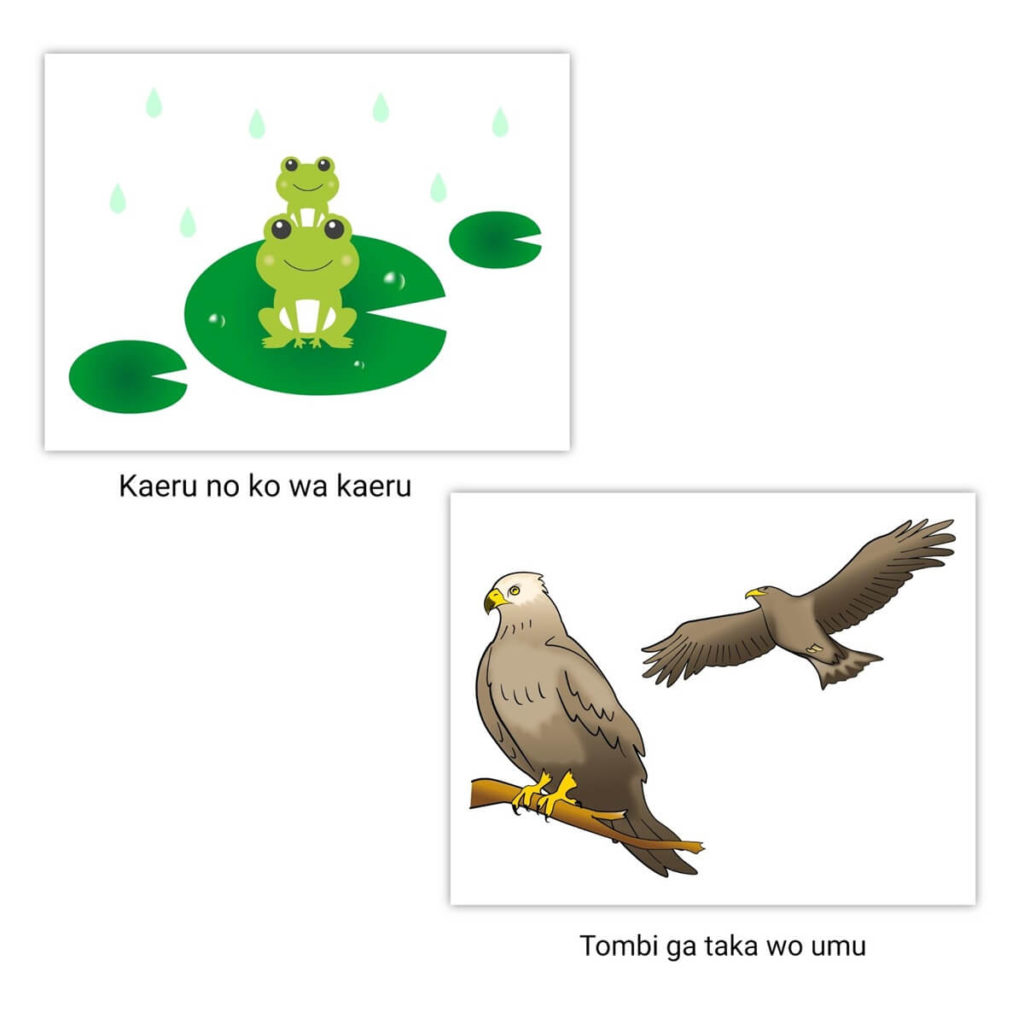

Imagine a boy who loved music when he was young, and everyone thought he might become a musician one day. But in the end, he followed in his father’s footsteps and took over the family business. In Japanese, there’s a saying for this: かえるの子はかえる (kaeru no ko wa kaeru), which literally means “A frog’s child is a frog.”

It’s used to show that children often take after their parents, whether in terms of career, personality, or lifestyle. In English, you’d say: The apple doesn’t fall far from the tree. Different images—frogs in Japan, apples in English—but the same idea. But can you guess why a frog? It’s because a tadpole looks nothing like a frog at first, but as it grows, it eventually becomes one. One thing to keep in mind is that this proverb not only means “children take after their parents,” but can also carry the nuance that “ordinary parents will only have ordinary children.”

There’s also a contrasting proverb in Japanese: 鳶が鷹を生む (tombi ga taka wo umu), which literally means “a kite gives birth to a hawk” (“kite,” in this case, refers to the bird). This one is used when a child turns out to be more talented or more beautiful than their parents.

Numerous proverbs refer to animals. The following two also include different animals but have the same meaning.

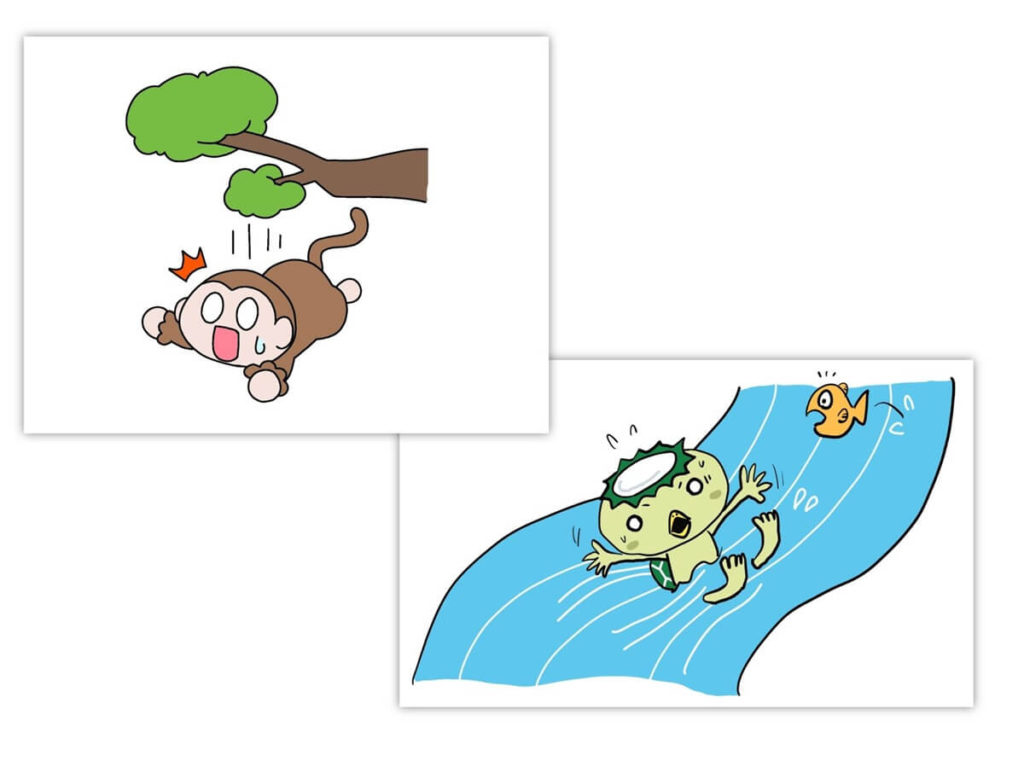

猿も木から落ちる (saru mo ki kara ochiru) : “Even monkeys fall from trees.”

河童の川流れ (kappa no kawa nagare): “Even a kappa can drown.”

The message is that even experts make mistakes. Interestingly, animals are used instead of simply saying “experts.” The meaning is easy to imagine when you describe the monkeys, who have a special talent for moving around in trees, and kappa, a sort of water goblin from Japanese folklore, which is said to be a good swimmer. It signifies that nobody is perfect, while also warning against complacency.

Here are three other animal-related proverbs that have a similar meaning.

The Japanese proverb 馬の耳に念仏 (uma no mimi ni nembutsu) literally means “a Buddhist sutra in a horse’s ear.” Imagine reciting sacred words to a horse; it wouldn’t understand anything. It’s like talking to a brick wall.

Figuratively, this expression is used when you say something meaningful or give advice, but the other person doesn’t listen or appreciate it. For example, when a parent warns a teenage daughter to save money, but that advice goes in one ear and out the other, and she goes shopping the next day, you could say it was 馬の耳に念仏 (uma no mimi ni nembutsu).

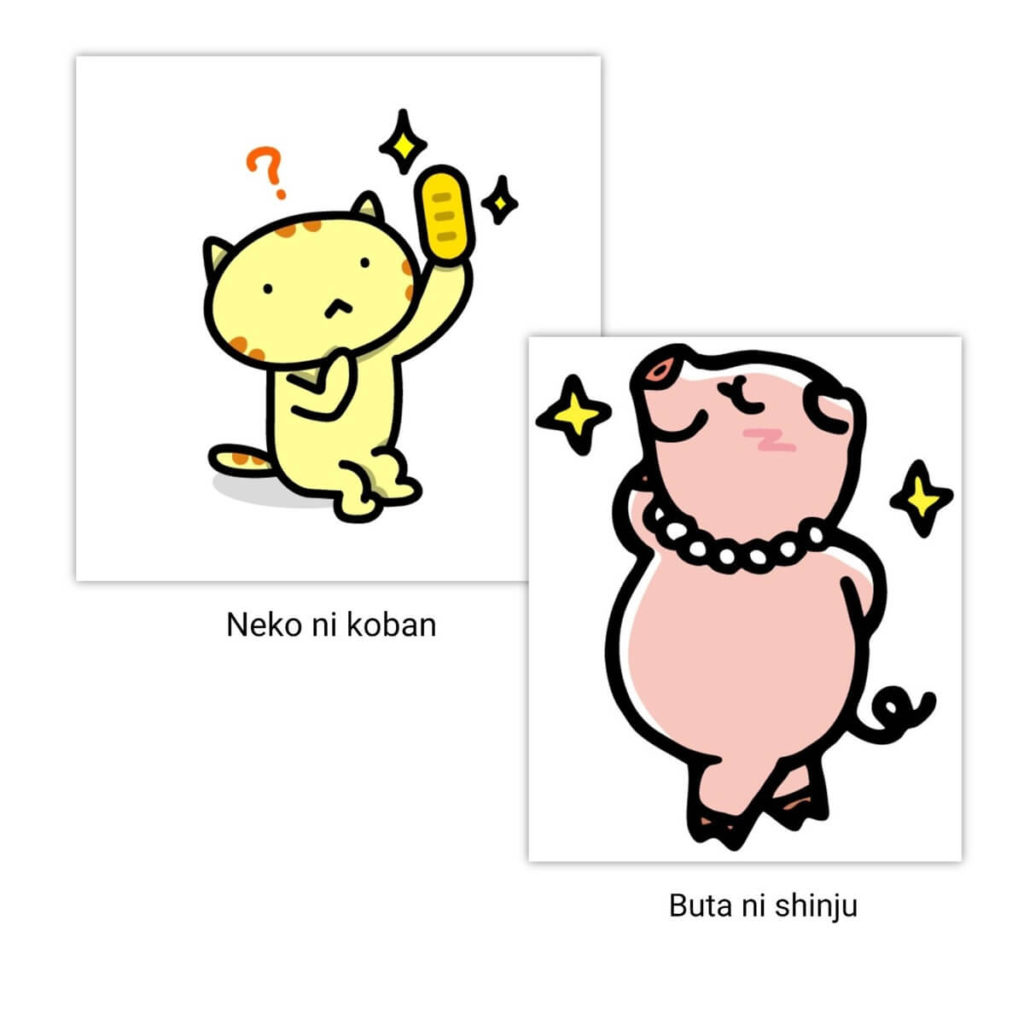

Another is 猫に小判 (neko ni koban), “gold coins for a cat.” Since a cat has no sense of the value of money, giving it coins is completely meaningless. For instance, to offer an expensive book to someone who never reads would be like 猫に小判 (neko ni koban).

Koban (小判) refers to an old Japanese gold coin, and the proverb seems to date back at least to the mid-Edo period in Japan. At this time, cats were familiar domestic animals but somewhat independent, stubborn, or uninterested in what humans considered valuable.

The last one is 豚に真珠 (buta ni shinju), “pearls before swine.” This expression originates from a biblical quote that illustrates the concept of “casting pearls before swine.” This means not to share Jesus’ teachings with those who will misuse them.

Now it describes giving something precious to someone who cannot recognize its worth. Imagine showing a rare piece of art to a friend who only shrugs and says, “So what?”— that’s exactly 豚に真珠 (buta ni shinju).

Though the imagery is different—horses, cats, and pigs—the message is the same: wisdom or treasures are wasted on those who don’t value them.

Next, I’d like to show you two proverbs related to food.

花より団子 (hana yori dango) literally means “dumplings over flowers.”

This proverb is based on the Japanese custom of viewing cherry blossoms. Some people care more about the food (dango) than the blossoms. In English, they don’t mention flowers or dumplings, but the meaning is the same: practicality over appearance.

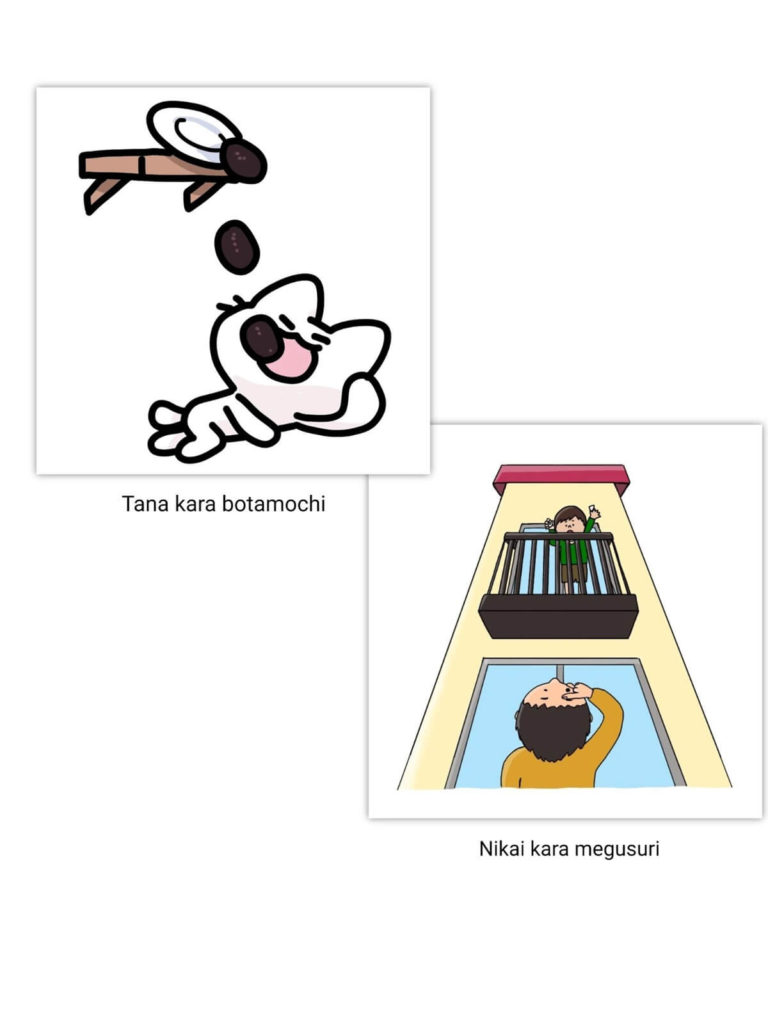

棚からぼたもち (tana kara botamochi ) literally means “a rice cake falls into your mouth from a shelf.”

It refers to receiving an unexpected stroke of good luck without any effort. Botamochi (ぼたもち) is a traditional Japanese sweet made from rice and red bean paste. The idea is that while you’re just sitting there, a delicious treat falls right into your lap (or even into your mouth). It’s a humorous image of effortless fortune. We often abbreviate it as “tanabota.”

Another proverb that has comical imagery is this:

二階から目薬 (nikai kara megusuri ) literally means “eye drops from the second floor.” Imagine that someone is standing on the second floor, trying to drip medicine into the eyes of a person below. It is a perfect metaphor for trying to help, but in such an ineffective way that it is almost in vain.

There are many more Japanese proverbs that I would like to share with you, but for now, let’s look at just one more. Last but certainly not least is the proverb that best represents Japanese culture.

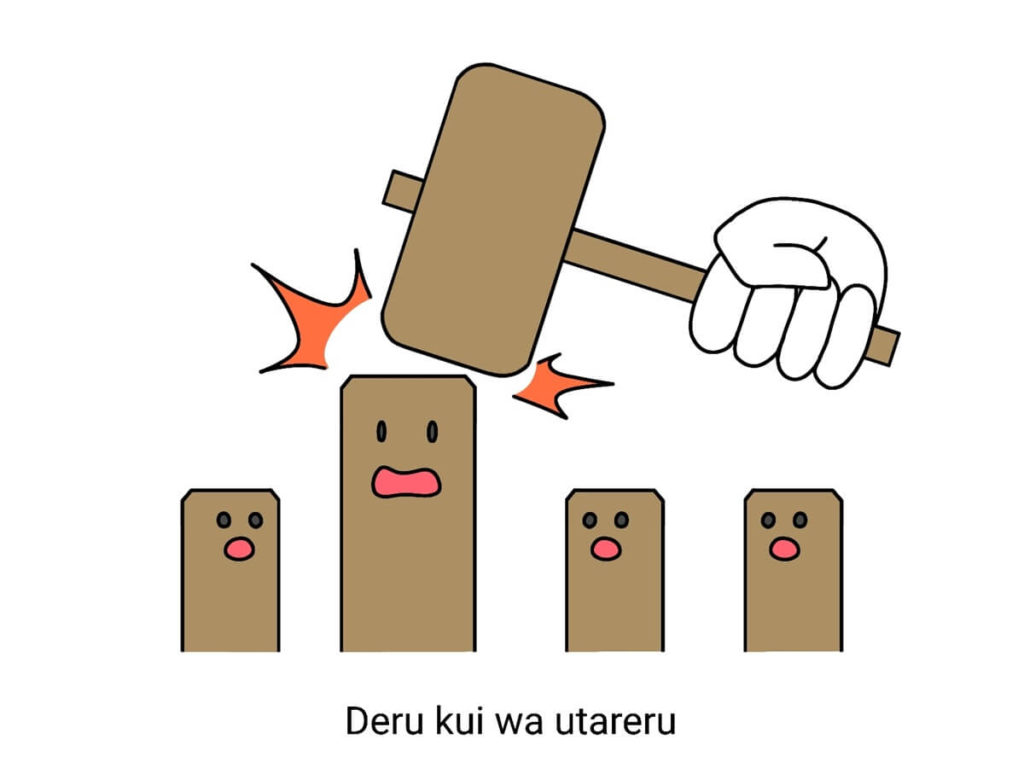

出る杭は打たれる (deru kui wa utareru) literally means “The nail that sticks out gets hammered down.”

It reflects the cultural tendency in Japan to value harmony and conformity, and to discourage people from standing out too much.

In contrast, there is a different emphasis in many Western cultures. While humility is still considered a virtue, success often comes from being unique and distinguishing yourself from others. In other words, standing out from the crowd is seen as a strength rather than something to be avoided.

Conclusion

Many Japanese proverbs have been passed down through a traditional card game called Iroha Karuta, which is especially popular as a New Year’s pastime. In the game, a reader (yomite) calls out a proverb or moral that begins with one of the 48 syllables of the old Japanese characters, and the players race to find and grab the corresponding picture cards.

Thanks to this game, many proverbs have survived and become part of everyday language. Iroha Karuta is not just entertainment but also a fun way to pass down culture and values across generations, and this is exactly the beauty of learning a language.

Lives in Takatsuki city, Osaka. Has been engaged in English for work and fun for years.

HTJ has a YouTube page! Check it out

HTJ has a YouTube page! Check it out